I’m a real sucker for manifestos about how to write. When I see an author offering bullet points, like commandments, about how to craft great prose or poetry, I can’t help myself: I devour them avidly.

I know, of course, that they’re often reductive and silly. “Most such rules are hogwash”, Ursula K Le Guin said back in 2015, “and even sound ones may not apply to your story. What’s the use of a great recipe for soufflé if you’re making blintzes?... Use only the advice that genuinely helps you get there.”

But I’ve long collected these guidelines, so here’s a sample of some of my favourites…

Most of you will know Kurt Vonnegut’s eight shibboleths:

Don't waste your reader's time.

Give the reader a character to root for.

Every character should want something. Even if it's only a glass of water.

Every sentence must either reveal character or advance the action.

Start as close to the end as possible.

Be a sadist. Make awful things happen to your characters. Let readers see what they're made of.

Write to please just one person.

Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible.

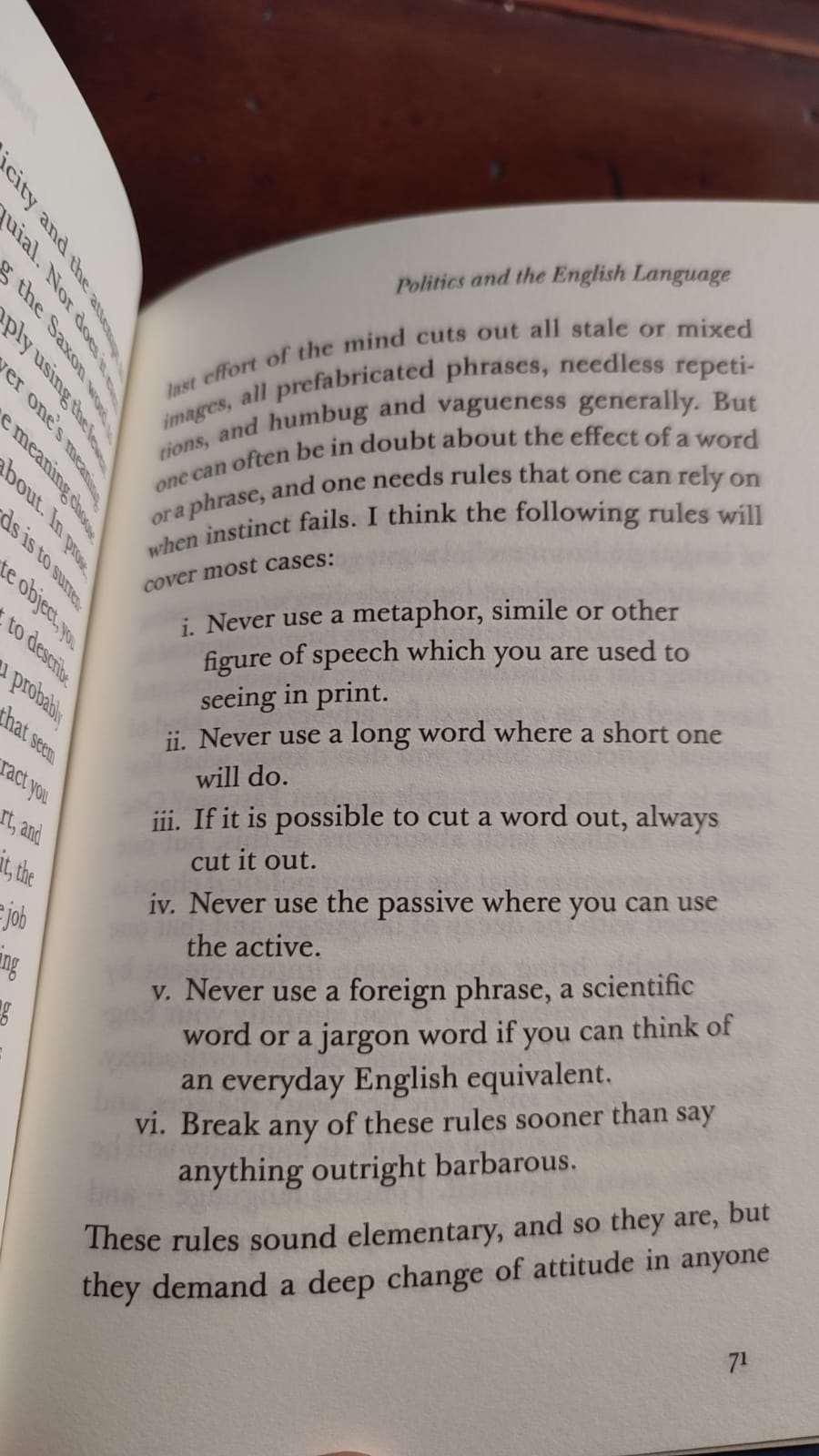

Over the coming weeks I’ll try to expand on some of these points, but by comparison, see what advice George Orwell offered in his essay, “Politics and the English Language”:

Often the advice I like is less about writing as such and more about how to remain creative. This is the famous advice forged by the great artist and nun, Corita Kent, along with the composer John Cage in the late 1960s:

Other manifestos are more punchy, beginning most sentences with a foreboding “never”. If you’ve read my essays and articles over the years, you’ll know that I love Elmore Leonard. He doesn’t mince his words:

Never open a book with weather.

Avoid Prologues.

Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said”.

Keep your exclamation points under control.

Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose”.

Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

His advice sounds a little odd sometimes (what’s wrong with opening a book with the weather? What on earth does “avoid detailed descriptions of characters” mean?!)… but if you read his extremely slight book (10 Rules of Writing) the explanations make a lot of sense.

Years ago, the Guardian took Leonard’s commandments as a prompt to ask various writers for their own manifestos. The replies veered from the profound to the deliberately counter-intuitive.

Diana Athill: “Cut… only by having no inessential words can every essential word be made to count.”

Margaret Atwood: “Hold the reader's attention.”

Roddy Doyle: “Do not place a photograph of your favourite author on your desk, especially if the author is one of the famous ones who committed suicide.”

Helen Dunmore: “Finish the day's writing when you still want to continue.”

Geoff Dyer: “Beware of clichés.”

Anne Enright: “The way to write a book is to actually write a book. A pen is useful, typing is also good. Keep putting words on the page.”

Richard Ford: “Marry somebody you love and who thinks you being a writer's a good idea.”

Jonathan Frantzen: “It's doubtful that anyone with an internet connection at his workplace is writing good fiction.”

Esther Freud: “Don't wait for inspiration. Discipline is the key.”

David Hare: “Style is the art of getting yourself out of the way, not putting yourself in it.”

PD James: “Write what you need to write, not what is currently popular or what you think will sell.”

A.L.Kennedy: “Write. No amount of self-inflicted misery, altered states, black pullovers or being publicly obnoxious will ever add up to your being a writer. Writers write. On you go.”

Hilary Mantel: “Concentrate your narrative energy on the point of change. This is especially important for historical fiction. When your character is new to a place, or things alter around them, that's the point to step back and fill in the details of their world. People don't notice their everyday surroundings and daily routine, so when writers describe them it can sound as if they're trying too hard to instruct the reader.”

Michael Morpurgo: “The prerequisite for me is to keep my well of ideas full. This means living as full and varied a life as possible, to have my antennae out all the time.”

Rose Tremain: “When an idea comes, spend silent time with it. Remember Keats's idea of Negative Capability and Kipling's advice to "drift, wait and obey". Along with your gathering of hard data, allow yourself also to dream your idea into being.”

Sarah Waters: “Cut like crazy. Less is more. I've often read manuscripts – including my own – where I've got to the beginning of, say, chapter two and have thought: ‘This is where the novel should actually start.’ A huge amount of information about character and backstory can be conveyed through small detail.”

Jeanette Winterson: “Turn up for work. Discipline allows creative freedom. No discipline equals no freedom.”

If you want to read the full advice from each of these, and various other, writers, the links to the two-part article are here and here.

All those writers come at the craft from different angles but there are lots of overlaps. The first insistent suggestion is the need to read voraciously and with discernment. Then – it’s kind of obvious - just get on with the actual writing. If we all spent as much time writing as we spoke and thought about writing, we would all be more productive. Many suggest keeping a diary, or always having a notebook on one’s person to log ideas and insights.

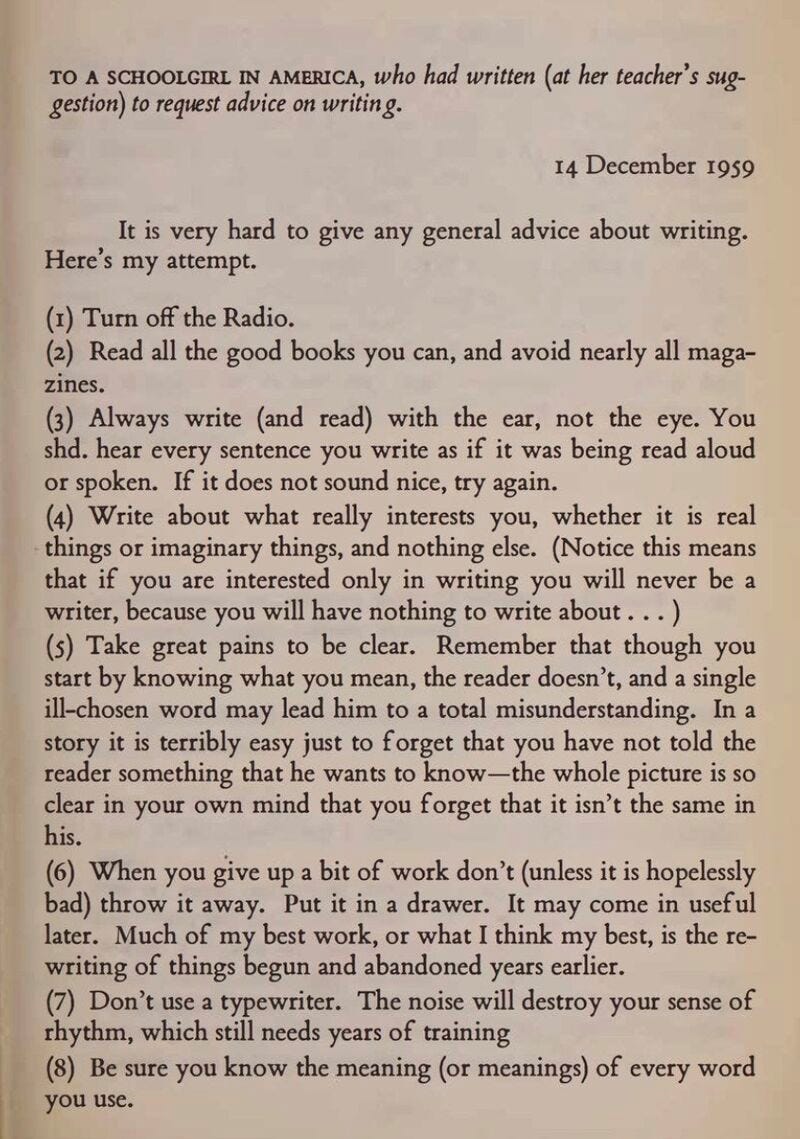

There are repeated injunctions to avoid an internet connection or – as C.S.Lewis wrote years ago in his letter to a young reader – to avoid the radio!

Many suggest how important it is to read out loud or to splurge onto the page in the early stages: use the hot brain to pour out words and only switch on the cold, critical brain later. As Cage and Kent wrote, “don’t try to create and analyse at the same time”.

Others insist on the importance of ignoring commercial expectations and all thoughts of sales or profits. As Ursula K. Le Guin said in this eloquent acceptance speech back in 2014: “the profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art… the name of our beautiful reward is not profit, its name is freedom.”

It’s intriguing, too, how much these mini-manifestos write of the need for humility, attentiveness, love, discipleship or discipline – terms which sound, to me, decidedly spiritual. People often think that writing is about imposing oneself on the world, but very often the experts suggest that it’s actually the opposite, an emptying out of oneself - what theologians would call kenosis.

But the advice which resonates most with me is the imperative to keep the reader engaged. “Don’t waste the reader’s time”, as Vonnegut says. That need to “hold the reader’s attention” (Atwood) is so often neglected: we insist on writing what the reader just wants to skip: we wander off into purple prose, into ornate description, into philosophical asides and the story itself gets lost. Leonard, quoting a Steinbeck character in Sweet Thursday, calls it “hooptedoodle”, the “spinning up of pretty words”. Cut, the experts repeatedly say. Cut, cut, cut.

But the joy of all these rules is that none of them are binding. Many manifestos (from Orwell to Kent&Cage) accept that all rules can be infringed. Writing, in the end, is about absolute freedom, which is why it’s so frightening and daunting.

And that, I guess, is why even the most famous truisms – “show, don’t tell”, “write about what you know”, “give us a character we can engage with”, “murder your darlings” – can be derided and dismantled. When “guides” for writers are “expanded into rules”, says Le Guin, “they are nonsense.”

Welcome to all new subscribers. Thanks for signing up. I try and publish a short essay each Sunday about writing. If you’re able, do please consider a paid subscription, and if you’re unable to do that, I'm grateful for just spreading the word. I’m trying to follow the rule not to write with money in mind, so being heard is as important as being paid!

I’d be interested to know which you strongly agree / disagree with and why.